Notes based on Class 8 NCERT History Chapter “Ruling The Country Side”” The Notes are comprehensive and exhaustive with headings, key points and summary points. Click here for notes of other chapters of Class 8 History.

1. The Company Becomes the Diwan

This Chapter focuses on how Company colonized countryside. Company’s role in shaping rural areas, asserting control.

- On 12 August 1765, Mughal emperor Sah Alam II appointed East India Company as Diwan of Bengal.

- Event possibly took place in Robert Clive’s tent with Englishmen and Indians as witnesses.

Diwan Responsibilities

- Company becomes chief financial administrator of controlled territory.

- Tasked with administering land and organizing revenue resources.

- Objective: Generate revenue to cover growing company expenses.

Dealing with Local Power

- Being an alien power, the Company needed to pacify previous local rulers, maintaining their authority to an extent.

- Control needed over local powers while not entirely eliminating them.

Organizing Revenue Resources

- Company takes on task of organizing revenue generation from the territory.

- Creating systems to collect taxes, manage resources effectively.

Redefining People’s Rights

- Company redefines rights of the local populace.

- Shift in power dynamics, altering traditional roles and relationships.

Manipulating Crop Production

- Company influences crop production to suit its needs.

- Shaping agricultural landscape for maximum profit.

Summary Points

- Company’s appointment as Diwan in 1765 marked significant shift in its role and responsibilities.

- Balance between trade interests and control over territory was a delicate task.

- Company had to manage local powers and reshape rural areas while generating revenue.

- Redefining rights and manipulating crop production were integral to Company’s strategies.

1.1. Revenue for the Company

Dual Identity: Company as Diwan and Trader

- Company held Diwan position but still considered itself a trader.

- Prioritized revenue while avoiding setting up regular assessment and collection systems.

Revenue Generation and Goods Acquisition

- Company aimed to increase revenue and acquire cotton and silk cloth inexpensively.

- Within five years, Company’s purchases in Bengal doubled in value.

- Earlier, Company imported gold and silver to buy goods; now Bengal revenue financed purchases.

Economic Crisis in Bengal

- Bengal economy faced significant crisis due to Company’s actions.

- Artisans left villages, compelled to sell goods at low prices to Company.

- Peasants struggled to meet imposed dues.

- Decline in artisanal production and signs of agricultural collapse emerged.

Impact of Famine

- In 1770, Bengal witnessed a devastating famine.

- Famine resulted in the death of ten million people, wiping out one-third of the population.

Summary Points

- Company, as Diwan, pursued revenue goals while maintaining its trading identity.

- Economic consequences of Company’s practices led to an adverse impact on Bengal’s economy.

- Negative effects included artisans’ migration, peasants’ struggles, and decline in agriculture.

- The 1770 famine further exacerbated Bengal’s crisis, causing immense loss of life and population reduction.

1.2. Permanent Settlement System

Ensuring Revenue Stability

- With the economy in disarray, the Company faced uncertainty in revenue.

- Realization grew that investment in land and agricultural improvement was crucial.

- After years of deliberation, Company implemented the Permanent Settlement in 1793.

- Settlement aimed to stabilize revenue collection and enhance agricultural productivity.

Recognition of Zamindars

- Permanent Settlement recognized rajas and taluqdars as zamindars.

- Zamindars were assigned the task of collecting rent from peasants and paying revenue to the Company.

Fixed Revenue and Incentives

- Under the settlement, revenue payments were fixed permanently and not subject to future increase.

- This approach ensured a steady revenue flow into the Company’s funds.

- Zamindars were encouraged to invest in land improvement due to revenue stability.

Mutual Benefits

- Permanent Settlement sought to balance the interests of both the Company and zamindars.

- Zamindars could benefit from increased land production as their revenue demand remained constant.

Summary Points

- Company recognized the need for agricultural enhancement to ensure consistent revenue.

- Introduction of Permanent Settlement in 1793 aimed to stabilize revenue and promote agricultural investment.

- Settlement established zamindars as intermediaries responsible for rent collection and revenue payment.

- Fixed revenue amount created incentives for zamindars to invest in land improvement and increased production.

1.3. The Problem with the Permanent Settlement

Lack of Zamindar Investment

- The Permanent Settlement led to unexpected issues.

- Zamindars did not invest in land improvement as intended.

- Fixed high revenue made it challenging for zamindars to make payments.

Consequences of Revenue Burden

- Failing to pay revenue led to zamindars losing their zamindari (landholding).

- Company organized auctions to sell off zamindaris due to non-payment.

Change in Situation

- By the early 19th century, market prices increased, and cultivation expanded.

- Zamindars’ income rose, but the fixed revenue couldn’t be increased.

Lack of Zamindar Interest in Improvement

- Zamindars still didn’t invest in land improvement.

- Some had lost lands earlier; others preferred easy income without investment.

- Zamindars profited from renting land to tenants rather than improving it.

Challenges for Cultivators

- Cultivators faced oppressive conditions under the system.

- High rent to zamindars and insecure land rights created difficulties.

- Loans from moneylenders often needed to pay rent.

- Failure to pay rent led to eviction from ancestral cultivated lands.

Summary Points

- The Permanent Settlement had unintended consequences.

- Zamindars failed to invest in land improvement due to high fixed revenue.

- Company auctioned off zamindaris due to non-payment.

- Zamindars benefited from renting out land rather than improving it.

- Cultivators faced challenges with high rent, insecure land rights, and indebtedness.

1.4. The Mahalwari Settlement

Need for Revenue Change

- By the early 19th century, Company officials realized the need to alter the revenue system.

- Fixed revenue wasn’t feasible as the Company required more funds for administration and trade.

Introduction of the Mahalwari Settlement

- In 1822, a new system was introduced in the North Western Provinces of Bengal Presidency (now mostly Uttar Pradesh).

- It was developed by Holt Mackenzie, an Englishman.

Preservation of the Village

- Mackenzie’s system aimed to preserve the importance of villages in North Indian society.

- Villages considered crucial social institutions.

Village-level Inspection and Assessment

- Collectors inspected villages, measured land, and documented customs and rights of various groups.

- Estimated revenue of each plot summed up to calculate village’s overall revenue.

Periodic Revision, Not Permanent Fixation

- Unlike the Permanent Settlement, revenue demand was not permanently fixed.

- Periodic revisions allowed adjustments based on changing circumstances.

Shift in Collection Responsibility

- The task of collecting and paying revenue shifted from zamindars to village headmen (local leaders).

Benefits and Legacy

- This new system was named the mahalwari settlement.

- Aimed to ensure fairer distribution of revenue burden and encourage investment in agriculture.

Summary Points

- Company officials recognized the need for a revised revenue system due to financial constraints.

- Holt Mackenzie introduced the mahalwari settlement in 1822 in the North Western Provinces.

- Villages were viewed as important entities and their customs and rights were documented.

- Revenue was calculated per village, with periodic revisions, and collection responsibility shifted to village headmen.

- Mahalwari settlement aimed to distribute revenue fairly and promote agricultural investment.

1.5. The Munro System: Ryotwari Settlement

- Shift from Permanent Settlement

- In British-controlled territories in the South, a departure from the Permanent Settlement concept occurred.

- A new system known as ryotwar (ryotwari) was devised.

- Initial Experimentation by Captain Alexander Read

- Captain Alexander Read experimented with the ryotwar system in areas acquired after conflicts with Tipu Sultan.

- Development by Thomas Munro

- Thomas Munro played a significant role in refining and extending the ryotwar system.

- This system gradually expanded throughout South India.

- Absence of Traditional Zamindars

- Read and Munro believed the South lacked traditional zamindars (landlords).

- Settlement needed to be established directly with cultivators (ryots) who worked the land for generations.

- Individual Field Survey and Revenue Assessment

- Ryots’ fields were meticulously and individually surveyed before determining revenue assessment.

- Paternalistic British Approach

- Munro’s approach emphasized the British acting as paternal figures.

- Aimed to safeguard and protect the ryots under their care.

Summary Points

- Munro system, also called ryotwari settlement, replaced Permanent Settlement in South India.

- Experimented initially by Alexander Read and later developed by Thomas Munro.

- Based on direct settlement with ryots (cultivators), not traditional zamindars.

- Emphasized individual field surveys and careful revenue assessment.

- Munro’s approach promoted British role as protectors of the ryots, maintaining a paternalistic stance.

1.6. All was not well: Challenges with the New Systems

Unforeseen Issues

- Soon after implementation of the new systems, it became evident that problems existed.

- Revenue officials, aiming to boost land income, set excessively high revenue demands.

Negative Impact on Peasants

- The high revenue demands placed a heavy burden on peasants.

- Many peasants were unable to pay the steep revenue, leading to difficulties.

Desertion of Countryside

- The consequences were dire: many ryots (cultivators) fled from rural areas.

- Desertion led to villages becoming abandoned in various regions.

Unmet Expectations

- Initial optimism among officials envisioned the new systems transforming peasants into prosperous, entrepreneurial farmers.

- However, this vision did not materialize as anticipated.

Summary Points

- Implementation of new revenue systems brought to light unforeseen issues.

- Overambitious revenue demands caused difficulties for peasants.

- High revenue led to ryots leaving rural areas, contributing to village desertion.

- Officials’ optimistic hopes of prosperous farmers didn’t align with the actual outcomes.

2. Crops of Europe

Cultivation for European Needs: British recognized potential of Indian countryside to not only generate revenue but also produce crops demanded by Europe.

Opium and Indigo Expansion: By late 18th century, East India Company aimed to expand opium and indigo cultivation.

Forced Cultivation and Expansion

- Over the following 150 years, British compelled or persuaded Indian cultivators to grow various crops.

- Introduced new crops in different regions: jute in Bengal, tea in Assam, sugarcane in United Provinces (Uttar Pradesh), wheat in Punjab, cotton in Maharashtra and Punjab, rice in Madras.

Methods for Crop Expansion

- British employed various approaches to promote cultivation of required crops.

- Techniques included encouraging farmers, providing incentives, introducing new farming methods, and using coercion if necessary.

Summary Points

- British saw Indian agriculture as a source for both revenue and crops for European needs.

- Expansion included opium, indigo, jute, tea, sugarcane, wheat, cotton, and rice cultivation.

- Methods to expand crop production varied, including persuasion, incentives, new techniques, and coercion.

- The passage hints at exploring a specific crop’s story to understand British influence on Indian agriculture.

2.1. Does Colour have a History? Indigo Dye

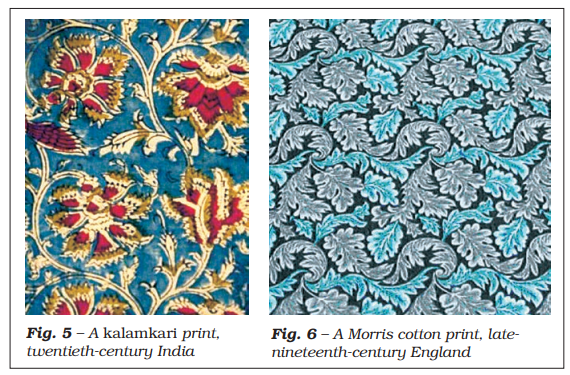

Comparing Cotton Prints: See below the two images of cotton prints: a kalamkari print from Andhra Pradesh, India (Fig. 5), and a floral print by William Morris from 19th-century Britain (Fig. 6).

Common Colour: Indigo: Both prints share a common feature: they use a deep blue colour, commonly known as indigo.

Indigo Dye Production: The blue colour seen in these prints was obtained from the indigo plant.

Source of Indigo: India played a significant role as the largest global supplier of indigo during that time.

William Morris’ Prints: It suggests that the blue dye used in Morris’ prints likely came from indigo plants cultivated in India.

Summary Points

- The passage explores the historical context of colour usage, particularly the blue indigo colour.

- It compares two cotton prints, one from India and one from Britain, both utilizing indigo dye.

- Indigo dye was extracted from the indigo plant, and India was a major source of indigo supply.

- The use of indigo dye in William Morris’ prints potentially involved dye from Indian indigo plants.

2.2. Why the demand for Indian Indigo?

Indigo’s Geographic Growth

- Indigo, primarily grown in the tropics, was used as a dye by European cloth manufacturers since the 13th century.

- Indian indigo was utilized, but its supply to Europe was limited, leading to high prices.

Competition with Woad

- European cloth makers relied on woad, a temperate zone plant, for violet and blue dyes.

- Woad was more accessible in Europe, grown in Italy, France, Germany, and Britain.

- Due to competition, woad producers influenced their governments to ban indigo imports.

Preference for Indigo Dye: Cloth dyers preferred indigo due to its richer blue colour compared to the paler and duller woad dye.

Expansion of Indigo Cultivation

- By the 17th century, European governments relaxed the ban on indigo imports.

- European powers established indigo plantations in various colonies: French in St. Domingue, Portuguese in Brazil, English in Jamaica, Spanish in Venezuela, and in parts of North America.

Industrialization and Growing Demand

- By the late 18th century, Britain’s industrialization and cotton production surged, causing a significant demand for cloth dyes.

- Existing indigo supplies from the West Indies and America dwindled due to various factors.

Supply Shortage and Search for New Sources

- Between 1783 and 1789, global indigo production dropped by half.

- British cloth dyers desperately sought new indigo sources.

Summary Points

- Indian indigo was in demand by European cloth manufacturers, but supply was limited and prices high.

- Woad was initially used as an alternative dye, but indigo’s rich colour preference led to relaxing bans on its import.

- European powers established indigo plantations in their colonies.

- Industrialization in Britain and increased cotton production escalated indigo demand.

- Shortage in existing supplies necessitated the search for new sources of indigo.

2.3. Britain Turns to India for Indigo Cultivation

Rising European Demand: With a growing demand for indigo in Europe, the East India Company sought ways to increase indigo cultivation in India.

Rapid Expansion in Bengal

- Starting from the late 18th century, indigo cultivation in Bengal experienced rapid growth.

- Bengal’s indigo production came to dominate the global market.

Shifting Import Statistics

- In 1788, around 30% of the indigo imported to Britain was from India.

- By 1810, this proportion significantly increased to 95%.

British Involvement in Indigo Production: As the indigo trade expanded, both commercial agents and Company officials became investors in indigo production.

Company Officials Becoming Planters: Many Company officials left their positions to engage in indigo business.

Scottish and English Planters: Attracted by the potential for high profits, numerous Scotsmen and Englishmen came to India and became indigo planters.

Financial Support: Those lacking funds for indigo production could secure loans from the Company or newly emerging banks.

Summary Points

- The East India Company aimed to meet Europe’s increasing indigo demand.

- Indigo cultivation in Bengal expanded rapidly and came to dominate the global market.

- Shift in indigo imports to Britain from India: 30% in 1788 to 95% by 1810.

- British commercial agents, Company officials, and newcomers invested in indigo production.

- Scots and English individuals were attracted to India to become planters due to the promise of high profits.

- Financial support for indigo production was available through Company loans and emerging banks.

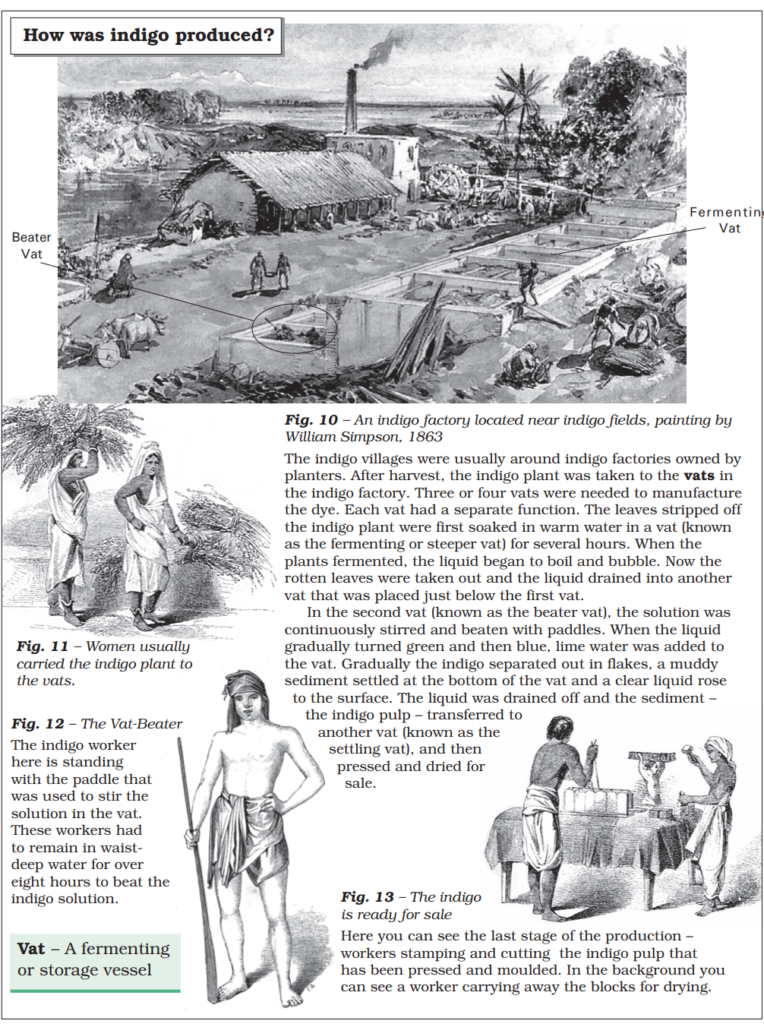

2.4. How was indigo cultivated?

Indigo Cultivation: Nij and Ryoti Systems: There were two primary systems of indigo cultivation: nij and ryoti.

Nij Cultivation

- In the nij cultivation system, the planter produced indigo on lands under his direct control.

- The planter could either own the land or rent it from other zamindars (landlords).

- Indigo production was managed by employing hired laborers directly.

Summary Points

- Indigo cultivation had two main systems: nij and ryoti.

- In the nij system, the planter controlled the land and either owned it or rented it.

- Indigo production under nij cultivation involved direct employment of hired laborers.

2.5. The problem with of Nij Cultivation

Expansion Challenges for Nij Cultivation

- Planters faced difficulties in expanding nij (directly controlled) cultivation of indigo.

- Indigo could only be grown on fertile lands, which were already densely populated.

- Obtaining larger plots for compact plantations was a challenge.

Land Acquisition Conflicts

- Planters tried to lease land around indigo factories and evict peasants.

- However, this approach often resulted in conflicts and tensions.

Labor and Resource Demands

- Large-scale nij cultivation required a significant workforce.

- Labor was needed during the time when peasants were busy with rice cultivation.

- Indigo cultivation also demanded many ploughs and bullocks, often clashing with peasants’ needs for their rice fields.

Investment in Ploughs

- One bigha of indigo cultivation needed two ploughs.

- Planters with large areas required substantial investments in purchasing and maintaining ploughs.

Ryoti System as an Alternative

- Due to challenges with nij cultivation, planters turned to the ryoti system as an alternative.

- Ryoti system involved cultivating indigo on lands worked by peasants.

Limited Nij Cultivation

- Until the late 19th century, planters were hesitant to expand nij cultivation.

- Less than 25% of indigo-producing land was under nij cultivation.

- The majority of indigo cultivation was carried out using the ryoti system.

Summary Points

- Expanding nij cultivation was difficult due to land scarcity and conflicts.

- Labor and resource demands for large-scale nij cultivation clashed with peasants’ rice cultivation needs.

- Ryoti system, involving peasants cultivating indigo on their own lands, emerged as an alternative.

- Less than a quarter of indigo cultivation land used nij cultivation, while the majority employed the ryoti system.

2.6. Indigo on the land of ryots

Contractual Agreements

- Under the ryoti system, planters coerced ryots (peasant cultivators) into signing contracts known as “satta.”

- In some cases, pressure was exerted on village headmen to sign on behalf of the ryots.

Contract Terms

- Signers received cash advances from planters at low interest rates to cultivate indigo.

- The contract committed the ryot to allocate at least 25% of their landholding for indigo cultivation.

Division of Labor: Planters provided seeds and drills while ryots prepared soil, sowed seeds, and tended to the crop.

Cycle of Loans and Harvest: After harvest, the ryot received a new loan from the planter, initiating another cycle.

Negative Realizations

- Initially enticed by loans, peasants recognized the harshness of the system.

- The income from indigo was minimal, and the cycle of loans was perpetual.

Land and Soil Issues

- Planters typically demanded indigo cultivation on the best soils, which peasants preferred for rice.

- Indigo’s deep roots rapidly depleted soil nutrients.

- After an indigo harvest, the land couldn’t be used for rice cultivation.

Summary Points

- Ryoti system involved contractual agreements between planters and ryots.

- Planters provided cash advances for indigo cultivation, leading to cycles of loans.

- Indigo exhausted soil, and its cultivation was often on lands preferred for rice.

- Peasants faced low income from indigo and suffered under the loan cycle.

- Indigo cultivation impacted soil fertility, rendering land unsuitable for rice after harvest.

3. The “Blue Rebellion” and After:

The “Blue Rebellion” and its Consequences

Ryot Resistance and Rebellion

- In March 1859, ryots in Bengal staged a rebellion against indigo cultivation.

- Ryots refused to grow indigo, stopped paying rents, and attacked indigo factories using weapons like swords, spears, bows, and arrows.

- Even women joined the fight using everyday tools.

- Those associated with planters were socially boycotted, and agents collecting rent were attacked.

Factors Behind the Rebellion

- The indigo system was oppressive, leading to the ryots’ dissatisfaction.

- Local zamindars and village headmen supported the rebellion, mobilizing indigo peasants and fighting against the planters.

- Some zamindars were unhappy with the increasing power of planters and their demands for land on long leases.

Expectations from British Government

- After the 1857 Revolt, the British government was concerned about popular uprisings.

- Ryots believed that the government would support them against planters due to this concern.

- Actions like a government tour, magistrate’s notices, and rumours of Queen Victoria’s declaration fuelled the perception of support.

Intellectual and Public Support: Calcutta intellectuals highlighted the ryots’ misery, planter tyranny, and the exploitative indigo system.

Government Response and Commission

- Government deployed military to protect planters and established the Indigo Commission to investigate indigo production.

- Commission found planters guilty, criticized their coercive methods, and declared indigo unprofitable for ryots.

- Ryots were allowed to refuse future indigo production and fulfil existing contracts.

Consequences and Shifts

- After the rebellion, indigo production collapsed in Bengal.

- Planters shifted to Bihar and faced further challenges with the advent of synthetic dyes in the late 19th century.

Champaran Movement: Gandhi’s visit to Bihar’s Champaran region in 1917 marked the start of a movement against indigo planters.

Summary Points

- “Blue Rebellion” in 1859 saw ryot resistance against indigo cultivation and oppressive planters.

- Ryots found support from local leaders, and perceived British government sympathy due to historical context.

- Intellectuals highlighted the plight, and government responded with military protection and an investigative commission.

- After the revolt, indigo production dwindled in Bengal but continued in Bihar.

- Synthetic dyes and Gandhi’s involvement impacted indigo planters and led to movements against them.