Clas 8 History Notes Chapter 6 Civilising the “Native”, Educating the Nation: The notes given here are well classified under headings and points. Enjoy the free notes and click here for other chapters of Clas 8 SST.

1. How the British saw Education

- The British perspective on education evolved significantly over the last two hundred years.

- British ideas about education in India and how Indians reacted to them played a crucial role.

- Orientalism, a movement that emphasized the study and appreciation of ancient Indian culture, influenced British thinking.

1.1 The tradition of Orientalism

- In 1783, William Jones arrived in Calcutta, known for his expertise in law and linguistic skills.

- Jones studied Sanskrit and delved into ancient Indian texts on various subjects.

- He, along with other British officials like Henry Thomas Colebrooke, established the Asiatic Society of Bengal and a journal called Asiatick Researches.

- Jones and Colebrooke shared a deep respect for both Indian and Western ancient cultures.

- They believed that understanding India required exploring its sacred and legal texts from ancient times.

- Their goal was to help the British learn from Indian culture and assist Indians in rediscovering their heritage.

- This project would make the British both guardians and masters of Indian culture.

Influence on Education Policies

- Some Company officials argued that the British should promote Indian learning over Western learning.

- They advocated for the establishment of institutions to study ancient Indian texts and teach Sanskrit and Persian literature and poetry.

- These officials believed that teaching what was familiar and valued by Hindus and Muslims would earn the respect of the “natives.”

- To implement this approach, a madrasa was founded in Calcutta in 1781 to promote Arabic, Persian, and Islamic law studies.

- The Hindu College was established in Benaras in 1791 to encourage the study of ancient Sanskrit texts useful for governing the country.

- Not all British officials shared these views, and many criticized the Orientalist perspective.

1.2: “Grave Errors of the East”

Criticism of Orientalist Vision:

- In the early nineteenth century, British officials criticized the Orientalist approach, branding it as full of errors and unscientific thoughts.

- Eastern literature was deemed non-serious and light-hearted, leading some to argue against encouraging the study of Arabic and Sanskrit.

James Mill’s Perspective:

- James Mill, among others, rejected the idea of catering to native preferences and respect.

- He advocated for education that focused on practical and useful knowledge, emphasizing scientific and technical advances from the West.

Thomas Babington Macaulay’s Influence:

- By the 1830s, criticism against Orientalists intensified, with Thomas Babington Macaulay emerging as a prominent voice.

- Macaulay viewed India as uncivilized and believed that Western knowledge far surpassed Eastern knowledge.

- He asserted the superiority of European literature, stating that a single European library shelf was worth more than the entire native literature of India and Arabia.

- Macaulay passionately advocated for teaching the English language, emphasizing its potential to expose Indians to the world’s finest literature, as well as developments in Western science and philosophy.

- He saw the teaching of English as a means to civilize Indians, transforming their tastes, values, and culture.

Impact and the English Education Act of 1835:

- Macaulay’s views influenced policy decisions, leading to the introduction of the English Education Act of 1835.

- The act mandated English as the medium of instruction for higher education, marking a shift away from Oriental institutions like the Calcutta Madrasa and Benaras Sanskrit College.

- These institutions were regarded as obsolete, and English textbooks started being produced for schools, aligning with the new emphasis on English education.

1.3 Education for Commerce

Wood’s Despatch (1854):

- In 1854, Charles Wood, the President of the Board of Control of the East India Company, issued an educational policy known as Wood’s Despatch.

- The Despatch highlighted the practical benefits of European learning over Oriental knowledge, emphasizing its economic and moral advantages.

Practical Benefits of European Learning:

Economic Advantages:

- European education would enable Indians to understand the benefits of trade and commerce expansion.

- It would introduce them to European lifestyles, changing their preferences and creating a demand for British goods.

Moral Improvement:

- European education was believed to enhance the moral character of Indians, making them honest and truthful.

- This moral development was seen as essential for producing trustworthy civil servants for the Company.

Rationale Behind the Emphasis on European Learning:

- Oriental literature was criticized for its errors and inability to instill a sense of duty, commitment to work, or administrative skills.

- European education was seen as a means to rectify these shortcomings and prepare a reliable administrative class.

Implementation of Policies:

Establishment of Education Departments: Education departments were set up by the British government to exert control over educational matters.

University Education: Efforts were made to establish universities in major cities like Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay, even amidst the backdrop of the 1857 revolt.

Changes in School Education:

- Reforms were attempted within the school education system to align it with the new educational policies.

- These policies and reforms marked a significant shift towards European-style education, emphasizing its practical applications in the realms of commerce, administration, and moral character development.

2. What Happened to the Local Schools?

2.1. The Report of William Adam:

William Adam’s Survey (1830s):

William Adam, a Scottish missionary, conducted a survey in the 1830s commissioned by the Company to assess vernacular schools in Bengal and Bihar.

Characteristics of Pathshalas (Local Schools):

- Adam identified over 1 lakh pathshalas in Bengal and Bihar, small institutions with about 20 students each.

- Despite the modest size, these pathshalas collectively educated over 20 lakh children.

- Pathshalas were established by local communities or wealthy individuals, often initiated by a guru (teacher).

Flexible Educational System:

Absence of Modern School Features: No fixed fees, printed books, separate school buildings, benches, chairs, blackboards, separate classes, roll-call registers, annual exams, or regular timetables.

Teaching Environment:

- Classes were conducted under banyan trees, in village shops, temples, or the guru’s home.

- Fee structure was based on parental income, ensuring accessibility for children of different economic backgrounds.

- Teaching methods were oral, with gurus deciding the curriculum based on students’ needs.

No Class Segregation:

- Students of varying learning levels sat together; there were no class distinctions.

- Gurus interacted individually or in groups based on students’ learning levels.

Adaptability to Local Needs:

- The system adapted to local demands; classes paused during harvest when rural children assisted in fields.

- Education resumed after harvest, allowing even children from peasant families to attend school.

Flexibility Suited to Local Needs:

- This flexible education system tailored itself to the agricultural rhythms and economic realities of the local communities.

- The absence of rigid structures allowed widespread participation, ensuring that education was accessible and adaptable to the varying circumstances of the people.

2.2 New Routines, New Rules

Company’s Focus on Vernacular Education:

- Until the mid-nineteenth century, the East India Company primarily concentrated on higher education, allowing local pathshalas to operate with minimal interference.

- Post-1854, the Company aimed to improve vernacular education by introducing order, routines, rules, and inspections into the system.

Company’s Different Measures:

(i) Appointment of Government Pandits:

- Government pandits were appointed, with each responsible for overseeing several schools.

- Pandits’ roles included visiting pathshalas, enhancing teaching standards, ensuring regular classes, and implementing a fixed timetable.

(ii) Standardization and Regularization:

- Gurus were required to submit periodic reports, follow textbooks, and conduct teaching based on a regular timetable.

- Learning was assessed through annual examinations.

(iii) Introduction of Fees and Fixed Seating:

- Students were expected to pay regular fees.

- They had to attend classes consistently, sit in fixed seats, and adhere to the newly established discipline.

(iv) Government Support and Competition:

- Pathshalas conforming to the new regulations received government grants.

- Independent gurus, desiring to maintain their autonomy, found it challenging to compete with regulated and government-aided pathshalas.

Impact on Poor Families:

- The new system’s discipline demanded regular attendance, including during harvest times when children from poor families traditionally worked in the fields.

- Inability to attend school due to agricultural commitments was viewed as indiscipline and a lack of desire to learn.

Consequences:

- Shift in Perception: Irregular attendance due to economic necessities came to be misinterpreted as a lack of interest in learning.

- Transformation of Pathshala Structure: Pathshalas, once flexible and accommodating, became more rigid, emphasizing regularity, examinations, fixed seating, and standardized curricula.

- Social and Economic Impact: Economic barriers and rigid schedules hindered the education of children from poor families, impacting their access to learning.

- Competition and Government Influence: Government-aided and regulated pathshalas gained prominence, overshadowing the independence of traditional gurus and their educational methods.

3. The Agenda for a National Education

3.1 “English Education Has Enslaved Us” – Mahatma Gandhi’s Perspective:

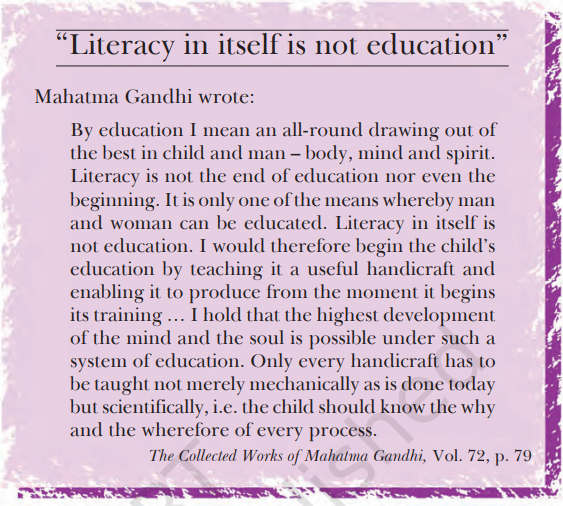

Critique of Colonial Education:

- Gandhi argued that colonial education instilled a sense of inferiority among Indians, making them view Western civilization as superior and eroding their cultural pride.

- He considered this education poisonous and enslaving, casting an evil spell on the Indian mindset.

- Educated Indians, enamored by the West, began to admire British rule, which Gandhi believed was detrimental to India’s self-respect.

Promotion of Indian Languages:

- Gandhi advocated for education in Indian languages, believing that English education alienated Indians from their social surroundings, rendering them strangers in their own land.

- Speaking a foreign language and disregarding local culture led to a disconnect with the masses, according to Gandhi.

Emphasis on Practical Knowledge:

- Gandhi criticized Western education for focusing solely on reading and writing, neglecting oral knowledge and practical skills.

- He stressed the importance of education developing a person’s mind and soul.

- Literacy alone did not constitute true education; Gandhi emphasized the significance of hands-on learning, craftsmanship, and understanding the practical aspects of different things.

Vision for a Different Education System:

- Gandhi proposed a form of education that went beyond textbooks and valued lived experience and practical knowledge.

- He encouraged people to work with their hands, learn crafts, and understand how things operated, believing that this approach would enhance their capacity to comprehend the world around them.

Nationalist Sentiments and the Call for a Radical National Education System:

- As nationalist sentiments spread, thinkers envisioned a national education system radically different from the British-established one.

- This period marked a shift towards redefining education in India, emphasizing self-reliance, cultural pride, and practical skills rather than subservience to colonial ideals.

3.2 Tagore’s “Abode of Peace”

Founding of Santiniketan:

- In 1901, Rabindranath Tagore established Santiniketan, a unique educational institution located 100 kilometers away from Calcutta.

- Tagore’s own unpleasant experiences with formal schooling as a child influenced his vision for education.

- He aimed to create a school where children could be happy, free, creative, and able to explore their thoughts and desires without the rigid constraints of British educational systems.

Tagore’s Vision of Education:

- Childhood as Self-Learning: Tagore believed childhood should be a period of self-learning, unrestricted by the harsh discipline imposed by British schooling.

- Imaginative Teaching: Teachers at Santiniketan were expected to be imaginative, understanding each child’s needs and fostering their curiosity.

- Creativity in Natural Environment: Tagore believed creative learning could flourish only in a natural environment. He chose a rural setting for Santiniketan, which he envisioned as an “abode of peace” (santiniketan) where children could live harmoniously with nature and nurture their creativity.

Convergence and Differences with Gandhi:

- Similarities: Both Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi shared ideas about fostering creativity and self-learning, emphasizing a harmonious connection with nature.

- Differences: Gandhi criticized Western civilization and its emphasis on machines and technology. In contrast, Tagore advocated combining aspects of modern Western civilization with the best of Indian tradition. He believed in teaching science, technology, arts, music, and dance at Santiniketan.

Debate on National Education:

- Varied Perspectives: Various individuals and thinkers contemplated the formation of a national educational system in India.

- Debate Continues: Discussions about defining “national education” persisted even after independence, with differing views on whether the existing British system should be modified or entirely new systems emphasizing true national culture should be established.

Important Images Given in Ihe Chapter.