Question & Answers of the class 8 NCERT History Chapter “Ruling the Countryside” are given here. All answers are of CBSE standard. Answers to ‘Activity’ Intext-Questions are also given. Click here for more study material.

Intext Activity Questions: Ruling the Countryside

Some ‘Activity’ titled questions are given in the chapter. The answers to such questions are given below.

Activity (Page 28)

Why do you think Colebrook is concerned with the conditions of the under-ryots in Bengal? Read the preceding pages and suggest possible reasons.

Ans: Colebrook expressed concern for the conditions of under-ryots in Bengal due to several reasons:

- Excessive Rent: Under-ryots were burdened by exorbitant rents imposed by powerful ryots. This hindered their ability to save and invest in improving their land or living conditions.

- Usurious Practices: Under-ryots faced exploitative practices, such as high charges for cattle, seed, and subsistence loans. These practices left them in perpetual debt, making it difficult for them to break free from poverty.

- Limited Progress: The dire financial situation of under-ryots prevented them from working diligently. Despite their labour, they earned barely enough to survive, leading to a lack of motivation for improvement.

- Hopelessness: Under-ryots felt trapped in their circumstances, without prospects for a better life. This hopelessness further discouraged efforts to improve their situation.

- Cycle of Poverty: The combination of high rents, usurious practices, limited earnings, and debt created a cycle of poverty that perpetuated their disadvantaged status.

In summary, Colebrook was concerned about the under-ryots’ plight in Bengal due to the oppressive economic conditions they faced, which hindered their ability to improve their lives and contribute to agricultural development.

Activity (Page 30)

Imagine that you are a Company representative sending a report back to England about the conditions in rural areas under Company rule. What would you write?

Ans. The report is given below:

To

The Honourable Directors of the East India Company

From: Ajeet Sir [Your Name]

Date: 08.08.2023 [Current Date]

Subject: Report on Rural Conditions Under Company Rule

Esteemed Directors,

I hope this report finds you in good health and high spirits. As per your request, I have meticulously observed and assessed the conditions prevailing in rural areas under Company rule. Allow me to present an overview of the situation for your esteemed consideration.

- Land and Agriculture:

The agrarian landscape in our territories is characterized by diverse farming practices. The peasantry remains largely dependent on subsistence agriculture, with traditional crops being the backbone of rural livelihoods. However, due to increasing demands for revenue and production, peasants often find themselves under pressure to allocate land for cash crops like indigo and other commodities, impacting food security. - Revenue and Taxation:

The Company’s introduction of various revenue systems, such as the Permanent Settlement and Mahalwari, has had both positive and negative repercussions. While these systems aimed to streamline revenue collection, issues of excessive taxation and arbitrary assessment remain persistent. The burden of revenue often outweighs the benefits reaped by the rural populace. - Labor and Exploitation:

There is a growing concern regarding the working conditions of laborers, especially in industries like indigo cultivation. Reports suggest that some planters are exploiting the labour force, resulting in cycles of debt and financial bondage. The welfare of laborers must be addressed to ensure fair treatment and just compensation. - Social Unrest and Resistance:

It is important to note that discontent among the rural population is brewing due to the Company’s policies and the implementation of certain revenue systems. Recent uprisings, such as the “Blue Rebellion,” underscore the potential for social unrest if grievances are not appropriately addressed. - Infrastructure and Development:

The Company has taken steps towards developing infrastructure in rural areas, including roads, irrigation systems, and communication networks. While these initiatives have improved connectivity, there is room for further investment to enhance the quality of life for rural inhabitants. - Cultural and Social Implications:

Company rule has had an impact on local customs, traditions, and social hierarchies. The engagement of local leaders and influential figures in governance has led to both cooperation and tensions, shaping the social fabric of rural communities.

In conclusion, our rule in rural areas is a complex tapestry of achievements and challenges. While we have made strides in certain areas, it is imperative that we remain committed to addressing the concerns of the rural population. Effective governance, equitable policies, and sustained development efforts are essential to foster harmony and ensure the well-being of those under our jurisdiction.

I remain at your disposal for any further inquiries or directives.

Yours faithfully,

[Your Name]

[Your Designation]

[Location]

Activity (Page 36)

Imagine you are a witness giving evidence before the Indigo Commission. W.S. Seton Karr asks you “On what condition will ryots grow indigo?” What will your answer be?

Answer:

To: W.S. Seton Karr, President of the Indigo Commission

Date: [Current Date]

Subject: Response to Question on Indigo Cultivation Conditions

Dear Mr. Seton Karr,

I appreciate the opportunity to provide my perspective as a witness before the Indigo Commission. In response to your question about the conditions under which ryots would be willing to grow indigo, my answer is as follows:

The sentiments expressed by Hadji Mulla reflect the deeply rooted concerns and grievances of the ryots regarding indigo cultivation. To address these concerns and create a more favourable environment for indigo cultivation, the following conditions could be considered:

- Fair Compensation: The ryots would be more willing to grow indigo if they receive fair compensation for their labour and produce. An equitable arrangement where the ryots are provided with reasonable rates for indigo bundles could encourage their participation.

- Debt Relief: Addressing the issue of debt bondage is crucial. Ensuring that the ryots are not burdened by exorbitant debts and that they have the means to repay loans without falling into cycles of perpetual indebtedness would be a positive step.

- Secure Tenure: Providing ryots with secure land tenure and protection from eviction would instil confidence in their decision to cultivate indigo. A sense of ownership and stability would motivate them to invest in the cultivation process.

- Working Conditions: Improving the working conditions on indigo plantations is essential. Proper facilities, reasonable working hours, and humane treatment of laborers would make indigo cultivation a more attractive option.

- Legal Safeguards: Implementing legal safeguards that ensure the ryots’ rights are protected throughout the cultivation process would build trust and encourage their participation.

- Technical Assistance: Offering technical guidance and support to ryots to enhance their indigo cultivation practices could improve yields and overall productivity.

It is important to note that the success of indigo cultivation hinges on creating a mutually beneficial partnership between the planters and the ryots. The above-mentioned conditions would help alleviate the historical grievances and apprehensions associated with indigo cultivation and create an environment where ryots may be more willing to participate.

Thank you for considering my input. I am at your disposal for any further inquiries or discussions.

Sincerely,

Ajeet Sir [Your Name]

[Your Designation]

[Location]

Exercise Question & Answers: “Ruling the Countryside”

Let’s Recall (Page 37)

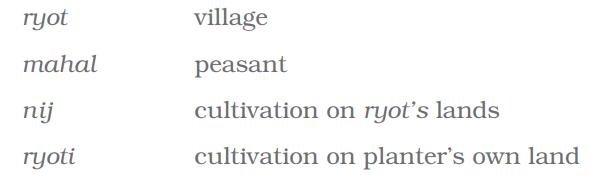

1. Match the following:

Answer:

- ryot: peasant

- mahal: village

- nij: cultivation on Planter’s own land

- ryoti: cultivation on Ryot’s lands

2. Fill in the blanks:

(a) Growers of woad in Europe saw ______ as a crop which would provide competition to their earnings.

(b) The demand for indigo increased in late eighteenth-century Britain because of ______.

(c) The international demand for indigo was affected by the discovery of ______.

(d) The Champaran movement was against ______.

Answer:

(a) Growers of woad in Europe saw indigo as a crop which would provide competition to their earnings.

(b) The demand for indigo increased in late eighteenth-century Britain because of expanding cotton production and industrialization.

(c) The international demand for indigo was affected by the discovery of synthetic dyes.

(d) The Champaran movement was against indigo planters.

Let’s Discuss (Page 37, 38)

3. Describe the main features of the Permanent Settlement.

Ans. The Permanent Settlement, introduced in 1793 during British colonial rule in India, aimed to establish a fixed revenue system for land taxation. It was initially applied in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. The main features of the Permanent Settlement were:

- Zamindars Recognized as Landowners: The British recognized existing zamindars (landlords) as the legal owners of the land. These zamindars were responsible for collecting revenue from peasants and paying a fixed amount to the British government.

- Fixed Revenue Obligation: The zamindars’ revenue obligation was fixed permanently and was not subject to change over time. This was intended to provide stability and predictability to the revenue collection process.

- Revenue Collection and Rent Payment: Zamindars were required to collect revenue from peasants and pay a predetermined amount to the British government. Any surplus collected beyond this fixed amount was their profit.

- Revenue Assessment: Initially, the revenue assessment was set based on historical land revenue data. It was often fixed at a high rate, pressuring zamindars to extract revenue from peasants to meet their obligations.

- Impact on Peasants: The Permanent Settlement had significant negative consequences for peasants. Since the revenue was fixed at a high rate, zamindars exerted pressure on peasants to maximize their income, leading to oppressive rent collection practices.

- Absence of Land Ownership Rights for Peasants: Peasants did not have ownership rights to the land they cultivated. They were essentially tenants of the zamindars and were subjected to exploitation.

4. How was the mahalwari system different from the Permanent Settlement?

Ans. The mahalwari system and the Permanent Settlement were two distinct revenue systems implemented by the British in India. Here are the key differences between them:

- Ownership and Revenue Responsibility:

- Permanent Settlement: Recognized existing zamindars as legal landowners responsible for revenue collection.

- Mahalwari System: Focused on the village or mahal as the revenue unit, with collective responsibility for revenue payments.

- Revenue Assessment:

- Permanent Settlement: Fixed revenue obligation imposed on zamindars, often at a high rate.

- Mahalwari System: Revenue assessment was done at the mahal level, with revenue shared among landholders within the mahal.

- Revenue Collection:

- Permanent Settlement: Zamindars collected revenue from peasants and paid a fixed amount to the British government.

- Mahalwari System: Revenue was collected collectively from the mahal and distributed among individual landholders.

- Ownership Rights for Peasants:

- Permanent Settlement: Peasants did not have ownership rights to the land and were subject to zamindar exploitation.

- Mahalwari System: Peasants had more direct involvement in revenue collection and shared ownership of the land within the mahal.

- Geographic Scope:

- Permanent Settlement: Initially applied in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa.

- Mahalwari System: Implemented in parts of North-Western Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh) during the early 19th century.

- Flexibility and Adjustments:

- Permanent Settlement: Fixed revenue obligation was permanent and not subject to change.

- Mahalwari System: Revenue demand could be revised periodically based on local conditions.

In summary, while the Permanent Settlement focused on zamindars and imposed a fixed revenue obligation, the mahalwari system cantered on collective revenue responsibilities at the village level, providing more flexibility and involvement for peasants.

Table of comparison:

| Aspect | Permanent Settlement | Mahalwari System |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership and Revenue Responsibility | Recognized existing zamindars as legal landowners responsible for revenue collection. | Focused on the village or mahal as the revenue unit, with collective responsibility for revenue payments. |

| Revenue Assessment | Fixed revenue obligation imposed on zamindars, often at a high rate. | Revenue assessment was done at the mahal level, with revenue shared among landholders within the mahal. |

| Revenue Collection | Zamindars collected revenue from peasants and paid a fixed amount to the British government. | Revenue was collected collectively from the mahal and distributed among individual landholders. |

| Ownership Rights for Peasants | Peasants did not have ownership rights to the land and were subject to zamindar exploitation. | Peasants had more direct involvement in revenue collection and shared ownership of the land within the mahal. |

| Geographic Scope | Initially applied in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. | Implemented in parts of North-Western Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh) during the early 19th century. |

| Flexibility and Adjustments | Fixed revenue obligation was permanent and not subject to change. | Revenue demand could be revised periodically based on local conditions. |

5. Give two problems which arose with the new Munro system of fixing revenue.

Ans. The Munro system, also known as the ryotwari system, had its own set of problems. Two of the main problems that arose with this system were:

- Uneven Distribution of Land and Revenue: The Munro system aimed to fix revenue directly with the cultivators (ryots). However, the distribution of land and revenue varied widely among ryots. Some ryots had large landholdings and paid high revenue, while others with smaller holdings faced difficulties in meeting the revenue demands.

- Inaccurate Survey and Measurement: The Munro system required accurate surveys and measurements of land to determine revenue. In practice, the surveys were often inaccurate, leading to disputes between ryots and revenue officials. Incorrect assessments of land could result in unjust and excessive revenue demands.

6. Why were ryots reluctant to grow indigo?

Ans. Ryots were reluctant to grow indigo due to several reasons:

- Exploitative Indigo System: The indigo system was oppressive, with planters forcing ryots to sign contracts and produce indigo. The contracts committed ryots to dedicate a portion of their land for indigo cultivation, impacting their ability to grow crops for sustenance.

- Low Returns: Ryots received minimal compensation for their indigo produce, often not commensurate with the efforts and costs involved in cultivation.

- Cycles of Debt: The indigo system involved cash advances from planters, which created a cycle of debt. Ryots found themselves trapped in debt, making it difficult to escape the exploitative system.

- Soil Exhaustion: Indigo cultivation depleted the soil rapidly, rendering it unsuitable for other crops like rice. Ryots relied on rice for their subsistence, and indigo cultivation threatened their food security.

7. What were the circumstances which led to the eventual collapse of indigo production in Bengal?

Ans. The collapse of indigo production in Bengal was influenced by several factors:

- “Blue Rebellion” of 1859: The ryot uprising against indigo cultivation in 1859, known as the “Blue Rebellion,” created widespread resistance against the exploitative indigo system, leading to a decline in cultivation.

- Support from Local Leaders: Local zamindars and village headmen supported the ryots’ rebellion against the planters, contributing to the decline of indigo production.

- British Government Intervention: The British government intervened by setting up the Indigo Commission, which found planters guilty of coercive methods and declared indigo production unprofitable for ryots. This undermined the viability of the indigo system.

- Shift to Bihar: Planters shifted their operations to Bihar after the rebellion in Bengal, but faced challenges there as well.

- Emergence of Synthetic Dyes: The discovery of synthetic dyes in the late 19th century posed a significant threat to indigo cultivation, as synthetic dyes offered more efficient and economical alternatives.

In combination, these factors led to the eventual collapse of indigo production in Bengal and the decline of the exploitative indigo system.

Let’s Do (Page 38)

8. Find out more about the Champaran movement and Mahatma Gandhi’s role in it.

Ans. More information about the Champaran movement and Mahatma Gandhi’s role in it:

The Champaran Movement and Mahatma Gandhi’s Role:

The Champaran movement was a significant episode in India’s struggle for independence, and Mahatma Gandhi played a pivotal role in it. The movement took place in the Champaran district of Bihar, India, during 1917.

Background:

- The British were forcing indigo cultivation on peasants in Champaran, similar to the exploitative indigo plantations of the past.

- Peasants were subjected to oppressive conditions and were compelled to cultivate indigo against their will.

Gandhi’s Involvement:

- Mahatma Gandhi, recently returned from South Africa and already known for his principles of nonviolent civil disobedience, arrived in Champaran in April 1917.

- He was invited by Rajkumar Shukla, a local farmer, to help the peasants in their struggle against the indigo planters.

- Gandhi decided to conduct a detailed inquiry into the situation and sought firsthand information from the affected peasants.

Key Features and Gandhi’s Role:

- Investigation: Gandhi met with villagers, listened to their grievances, and gathered evidence of the oppressive conditions they were facing.

- Satyagraha: He initiated a campaign of nonviolent resistance, or “satyagraha,” against the indigo planters and the British authorities. This marked one of the earliest instances of Gandhi’s use of nonviolent protest in India.

- Legal Battles: Gandhi was arrested by the British authorities, but he continued to lead the movement from prison. He successfully defended himself in court during his trial.

- Settlement: Under pressure from the growing movement and the public sympathy it garnered, the British government set up an inquiry committee, which ultimately recommended changes in the indigo system.

- Success and Impact: The Champaran movement led to significant reforms in the indigo plantations and raised awareness about the power of nonviolent resistance. It marked a turning point in Gandhi’s leadership and the broader struggle for India’s independence.

9. Look into the history of either tea or coffee plantations in India. See how the life of workers in these plantations was similar to or different from that of workers in indigo plantations.

Ans. Similarities and dissimilarities between workers in tea or coffee plantation and indigo plantations is given below:

Tea and Coffee Plantations in India and Workers’ Lives: Similarities:

- Like indigo plantations, tea and coffee plantations were established by the British colonial powers and often operated under exploitative conditions.

- Workers on these plantations, often indigenous or marginalized communities, faced harsh working conditions, low wages, and lack of basic rights.

- All three industries relied on forced labour, debt bondage, and exploitative contracts, leading to cycles of indebtedness.

Differences:

- In the case of tea and coffee plantations, workers had to tend to the plants over extended periods, whereas indigo cultivation was relatively short-term.

- Tea and coffee plantations faced issues related to long hours of work, low wages, and inadequate living conditions, but their products were not as synonymous with oppression as indigo was.

- The decline of indigo was primarily due to external factors like synthetic dyes, while tea and coffee continued to be produced and traded globally, adapting to changing market demands.

In summary, while tea, coffee, and indigo plantations shared some exploitative aspects in the treatment of workers, there were also differences in terms of the crops’ economic significance, working conditions, and the overall trajectory of the industries.

Let’s Imagine (Page 38)

Imagine a conversation between a planter and a peasant who is being forced to grow indigo. What reasons would the planter give to persuade the peasant? What problems would the peasant point out? Enact their conversation.

Ans. An imaginary such conversation is given below:

Planter: Good morning, my friend. I see you’re working hard in your fields. How about considering something new? Have you ever thought about growing indigo?

Peasant: Good morning, sir. Well, to be honest, I have heard about indigo, but I’m not sure if it’s the right choice for me. I’ve been growing my crops for years, and they’ve provided for my family.

Planter: I understand your concern, but let me tell you, indigo has its advantages. First, it’s in high demand in the market. The British are looking for indigo, and you could benefit from that demand.

Peasant: But sir, what about the crops I grow for my family’s consumption? Indigo would require a portion of my land, and I worry that it might affect our food supply.

Planter: I understand your concern, but think about the profits. Indigo brings in good money. I can provide you with advanced cash to help you with the initial investment. You’ll have extra income to support your family.

Peasant: That does sound tempting, but I’ve heard stories about the contracts and conditions imposed on indigo cultivators. I’ve heard about the debts that keep piling up and the harsh treatment by overseers.

Planter: Those are just rumours, my friend. We have modern methods and a fair system in place. I assure you that we’ll treat you well, and the contracts are just to ensure a steady supply. With our guidance, you’ll find indigo cultivation profitable.

Peasant: I appreciate your reassurance, sir, but I’m concerned about my land’s fertility. I rely on this land to feed my family, and I don’t want to risk depleting the soil.

Planter: Your concerns are valid, but indigo can coexist with your other crops. We’ll provide the necessary resources and support to ensure sustainable cultivation practices.

Peasant: And what about the debt? I’ve heard that once you’re in, it’s hard to get out. Many families have suffered because of it.

Planter: I won’t deny that there have been challenges in the past, but we’re committed to fair practices now. You’ll have the opportunity to clear your debts and still earn a decent living.

Peasant: I appreciate your offer, sir, but I need time to think. My family’s well-being is my priority, and I need to consider all the implications before making such a big decision.

Planter: Of course, I understand. Take your time to think it over. Just remember that we’re here to support you and your family’s prosperity. Indigo cultivation could be a stepping stone towards a better future.

Peasant: Thank you for understanding, sir. I’ll discuss it with my family and consider the options carefully.

[Conversation ends]